Haemoptysis

Introduction

Haemoptysis is the expectoration of blood, sometimes mixed with saliva or sputum, from the lungs or tracheobronchial tree.

There are many causes for haemoptysis (see below), however no cause is identifiable in around 30% of cases. A thorough history and exam should help to identify underlying causes.

Most patients present with small volume haemoptysis (< 20ml per 24 hours) and tend to be stable on presentation. A small percentage (~2%) present with massive haemoptysis which can quickly result in respiratory or cardiovascular compromise. Massive haemoptysis has a mortality rate of up to 80% and is defined as expectoration of a volume of blood that is significant enough to be life threatening by virtue of airway obstruction or blood loss. The most common causes of massive haemoptysis are lung malignancies and chronic inflammatory conditions such as TB, bronchiectasis and pulmonary abscesses.

Causes of Haemoptysis

It is important to differentiate haemoptysis from haematemesis, oral bleeding or nasopharyngeal bleeding i.e. that the blood was coughed up by the patient and is not from an other sources.

Pulmonary

Infection

Pneumonia

Tuberculosis

Lung Abscess

Bronchiectasis including cystic fibrosis

Neoplasm (primary or metastatic)

PE with pulmonary infarction

Trauma, foreign body

Connective Tissue Disease

Arteriovenous malformation

Extra Pulmonary

Oral e.g. dental, nasal or tongue bleeding

Pharyngeal e.g. Tonsillitis

GI Bleed

Cardiac

Acute pulmonary oedema/CCF

Mitral stenosis

Vascular e.g. aortic dissection

Bleeding disorders

Drugs e.g. Cocaine

Clinical Features

Symptoms

Infectious symptoms

cough, fever

Pain (often pleuritic)

Fatigue

Weight loss

Night sweats

Symptoms to suggest extrapulmonary causes e.g. recent vomiting, sore throat

Signs

May have nil of note to find on exam

Signs of airway obstruction

resp distress, stridor, gurgling respirations, hypoxia, cyanosis

Signs of shock

hypotension, tachycardia, altered conscious state, peripherally shut down

Respiratory signs

hypoxia, clubbing, tachypnoea, wheeze, crackles

Signs of systemic illness

pallor, cachexia

Signs of extra-pulmonary cause e.g. cardiac, abdominal, oropharyngeal signs.

Clinical Investigations

Bedside

Arterial Blood Gas (if Hypoxic)

?Respiratory Failure. Hb, Lactate, BM, Electrolytes

ECG

Cardiac cause for symptoms

Laboratory

FBC, CRP, blood culture if ?sepsis or infectious cause

Group and Hold/Crossmatch in severe cases

Coagulation screen

U&E,

Bone profile + LFTs

may show abnormalities in some malignancies

Sputum culture (If concerns regarding infection including TB) + Urinary antigens if ? pneumonia

not routinely done in ED but may be organised by admitting team.

Radiology

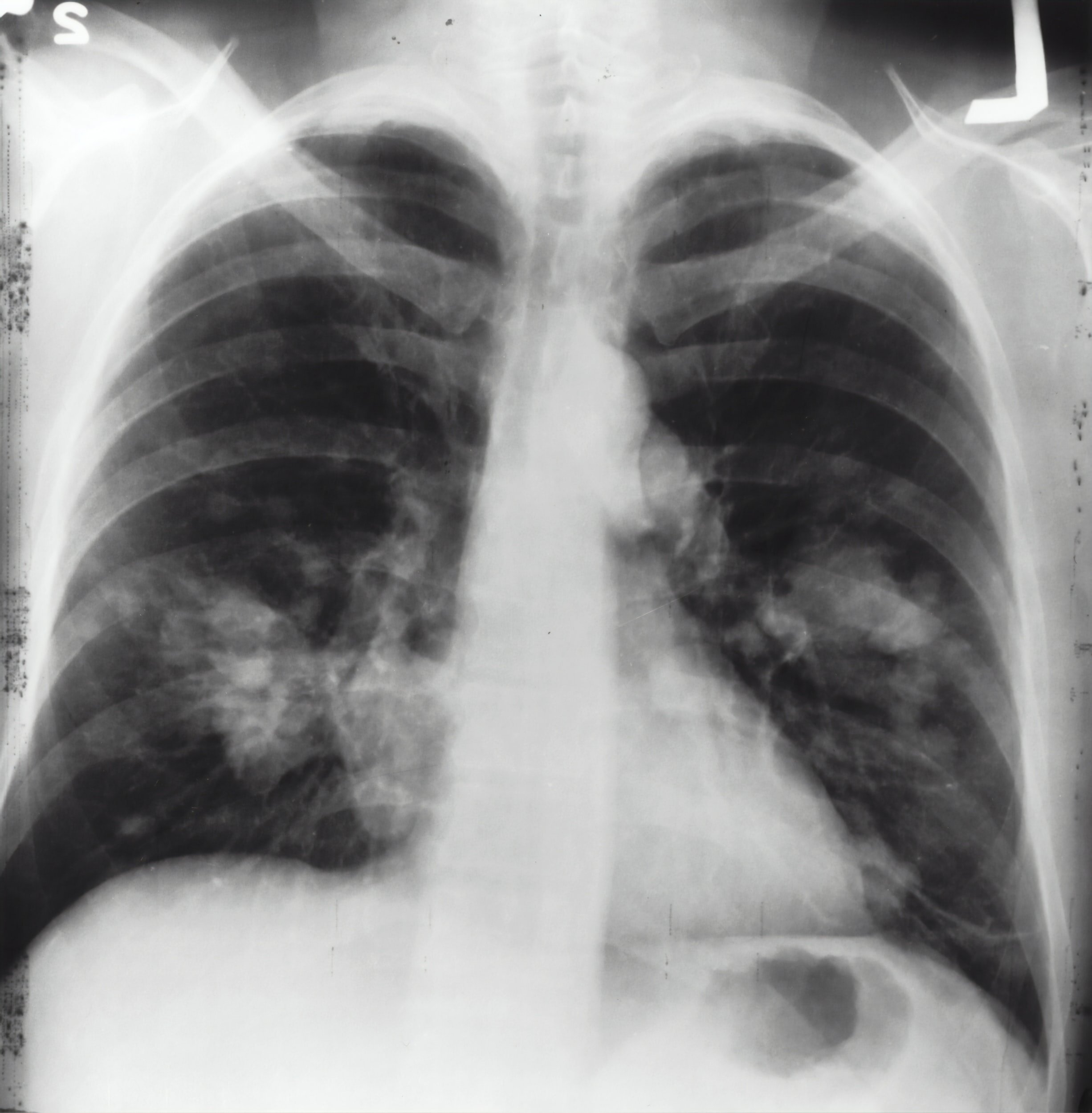

CXR

May identify an underlying cause. 20-30% will have normal CXR

CT

CT Thorax with contrast screening test of choice for ? malignancy, ? AVM, ? abscess. Further investigations may be needed to confirm diagnosis e.g. biopsy. IV contrast can demonstrate is there is active bleeding

CTPA if ? PE.

Bronchoscopy

Investigation of choice in cases where an abnormality of the bronchial tree is suspected

Direct visualisation and biopsy

In cases of massive haemoptysis therapeutic interventions can be done under direct vision via bronchoscopy as outline below.

Management & Disposition

Initial Resuscitation

Massive Haemoptysis

Resuscitation as required, following ABCs

nurse the patient lying on their side with the bleeding lung (if known) down, or in trendelenberg position

Airway compromise can occur quickly in massive haemoptysis

Suctioning & Oxygen as required for Sats >94%

Early intubation with large bore ETT if airway concerns.

consider double lumen tube if skilled operator and aware what side the lung pathology is

Declare CODE RED and commence warmed IV blood products if evidence of cardiovascular collapse

Specific Treatment

Massive Haemoptysis

Treatment depends on the patient and the source of bleeding

in those patients with advanced lung cancer invasive treatments may not be in their best interests.

Topical adrenaline or endobronchial balloon tamponade at bronchoscopy with respiratory physicians

Bronchial artery embolization with interventional radiology

Ongoing bleeding may warrant thoracotomy +/- partial or complete lobectomy with cardiothoracic surgeons.

Mild/Moderate Haemoptysis

Seek and treat underlying cause is generally only treatment required

e.g. antibiotics for infection, treat CCF etc

Disposition

Mild haemoptysis can usually be discharged from the ED with outpatient follow up

very important to have tight follow up. e.g. Rapid Access Lung Clinic if any possibility of underlying malignancy

Moderate haemoptysis should be admitted for inpatient work up and treatment of underlying pathology.

Massive haemoptysis patients if they survive initial insult will require ongoing airway and ventilatory management in ICU

References

Cham G ,Cameron P. et al. Chapter 6.8 Haemoptysis. Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine. 4th Edition

Dixon J, Cline D. et al. Chapter 33 Haemoptysis. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine Manual, 7th Edition

Case courtesy of Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 8524

This blog was written by Dr Robert Evans and was last updated in February 2021