Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Introduction

Pneumothorax means air in the pleural cavity. Pneumothoraces are either spontaneous, traumatic or iatrogenic in origin. Traumatic & iatrogenic pneumothoraces will be dealt with elsewhere. From here on we will discuss only spontaneous pneumothoraces on this page.

Spontaneous pneumothoraces are generally split into two groups, primary spontaneous pneumothoraces which are pneumothoraces which occur in patients without underlying lung disease, and secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces which occur in patients with underlying lung diseases such as COPD or TB.

Risk Factors

Smoking is strongly associated with the development of pneumothoraces and pneumothoraces in non-smokers are exceedingly rare (1).

Risk factors for development of pneumothoraces include;

Smoking, both cannabis and tobacco

Genetic predisposition.

Secondary pneumothoraces are associated with a number or underlying lung diseases including (2);

COPD

Tuberculosis

Cystic fibrosis

Necrotising lung infections ie: PJP

Lung malignancies

Thoracic endometriosis

Clinical Features

Spontaneous pneumothoraces range in presentation from small apical pneumothoraces in patients with no underlying lung disease causing little or no symptoms, right up to tension pneumothorax which is a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate intervention.

Generally speaking patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax tend to be more symptomatic than those with primary pneumothoraces and patients with secondary pneumothoraces tend to be more compromised with relatively smaller pneumothoraces due to their reduced lung reserve.

Symptoms

Shortness of breath – the symptom which best correlates with the size of the underlying pneumothorax

Pleuritic chest pain

Dry cough

Signs

Respiratory compromise – the degree of compromise depends on the size on the pneumothorax and severity of underlying lung disease

Tachypnoea

Accessory muscle use

Low sats

Reduced air entry

Hyper-resonant to percussion

Tachycardia

Tension pneumothorax

Elevated HR, low BP

Distended neck veins

Tracheal deviation

Differential Diagnosis

Respiratory

Pulmonary embolism

Pneumonia

Exacerbation of COPD / asthma

Cardiovascular

Pericarditis

Myocardial infarction

Other

Musculoskeletal pain - this is a diagnosis of exclusion

Clinical Investigations

Bedside

12 lead ECG

May be normal or show sinus tachycardia in pneumothorax

Useful to rule out other differentials, ie pericarditis

Arterial blood gas if O2 sats are low, otherwise venous gas is adequate

Shows degree of hypoxia

May show hypercapnia & acidosis if significantly compromised

Point of care lung ultrasound – rule in investigation

Inter-operator variability reduces usefulness

Most commonly used in trauma patients who must remain supine and will show

Absent lung sliding

Absent B-lines

Barcode sign on M mode

Presence of transition point

Laboratory

Laboratory investigations are not that useful in the initial diagnosis and management of spontaneous pneumothorax however they are useful in ruling out other causes and in patients with concomitant problems such as infection.

FBC

May show elevated WCC – non-specific

CRP, U/E, LFT’s, Coag screen, troponin

Useful to rule out other differentials

Radiology

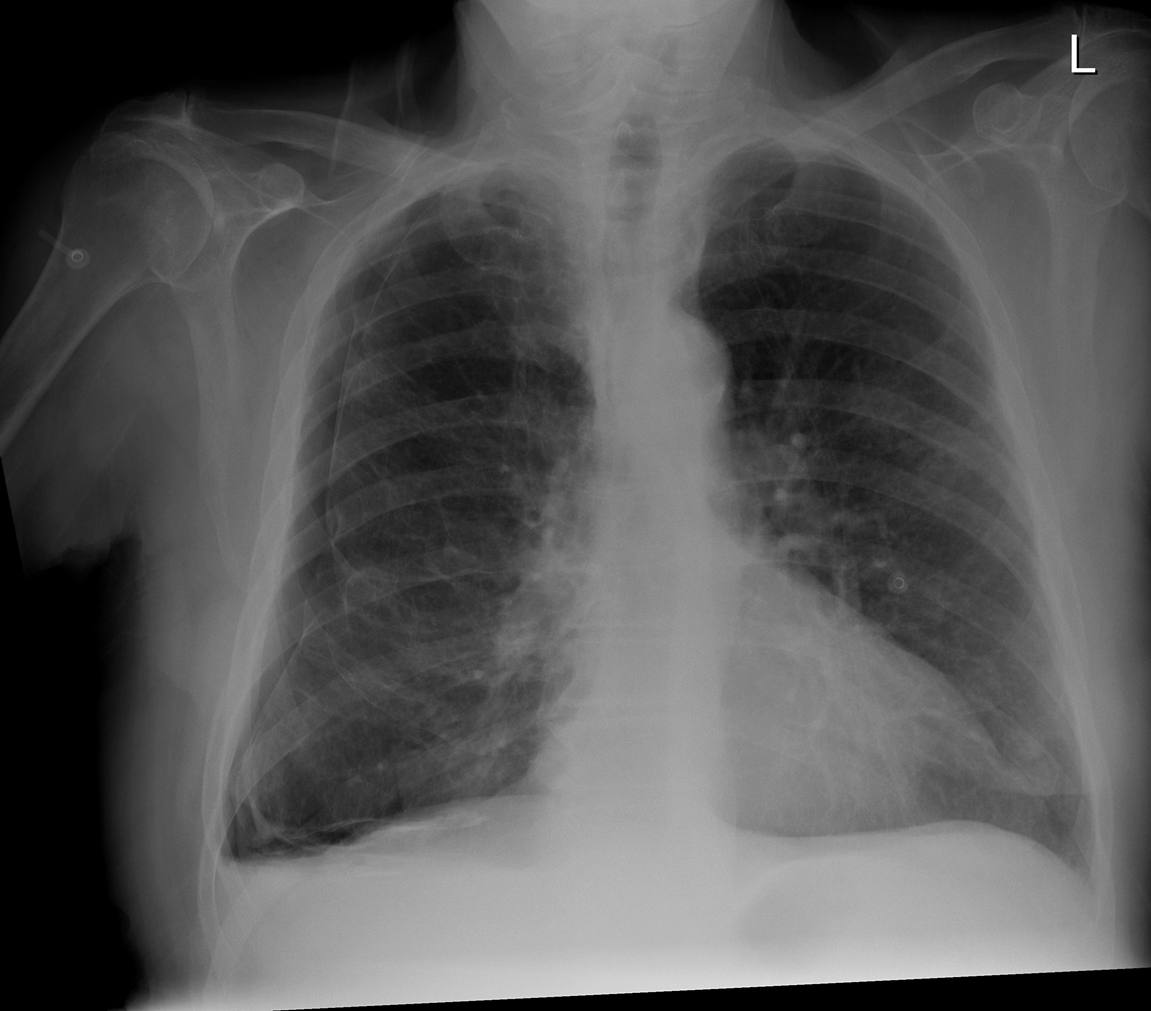

Chest x-ray

Initial investigation of choice due to ease of access

Difficult to accurately quantify the size of pneumothorax on chest x-ray

Large bullae may mimic pneumothoraces. If any doubt about the diagnosis CT thorax should be performed

Small apical pneumothoraces sometimes may be missed on traditional chest x-rays

CT Thorax

Considered gold standard for diagnosis and size estimation

Useful to rule in or out alternative diagnoses including bullae which can sometimes mimic pneumothorax

Management & Disposition

Haemodynamically unstable patients should be assessed and managed with a standard ABC approach. Patients who are haemodynamically unstable because of a tension pneumothorax should have immediate needle decompression followed by urgent chest drain insertion.

The traditional approach to needle decompression is insertion in;

Anterior chest wall

Mid-clavicular line

2nd intercostal space

Just above the inferior rib (avoids intercostal bundle)

Recently there is some debate of the best location for decompression however that is beyond the scope of this blog

Stable patients should be managed in accordance with the British Thoracic Societies guidelines on the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. The advice differs depending on whether the patient has a primary or secondary pneumothorax.

Any patients who are discharged from the ED either with no intervention or after aspiration of spontaneous pneumothorax should be given careful written and verbal discharge advice and should be booked into an clinic, ideally within 1 week for repeat x-ray and follow-up.

Discharge advice should include advice about

Planned follow-up

What to do if they become more unwell

Advice on what to avoid until planned follow-up;

Avoid Scuba diving (lifelong advice)

Avoid flying until pneumothorax has fully resolved

References

MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010; 65(18).

Light RW, Lee G. Pneumothorax in adults: Epidemiology and etiology. [Online].; 2020 [cited 2020 October 25. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pneumothorax-in-adults-epidemiology-and-etiology?search=spontaneous%20pneumothorax&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

This blog was written by Dr. Emer Kidney and was last updated in November 2020