Acute Exacerbation of COPD

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is characterised by irreversible airflow obstruction which can be acutely exacerbated. While two distinct phenotypes exist, either dominated by chronic bronchitis or emphysema, the acute management of an exacerbation is the same regardless.

The single biggest risk factor for COPD is smoking, though environmental exposures and air pollution also play a part. The incidence of COPD typically increases with age.

Most exacerbations of COPD are caused by a bacterial or viral lower respiratory tract infection thought some are non-infectious in origin and may be caused by environmental triggers.

Long term management of COPD includes short and long acting beta agonists , muscarinic antagonists and inhaled corticosteroids in various combinations as dictated by the patient’s baseline pulmonary function and symptoms. Patients may also have nebulised short acting bronchodilators at home for regular or occasional use. In patients with severe disease, long term oxygen therapy (LTOT) at home is often used either continuously or intermittently.

The chronic management of COPD is beyond the scope of this article, however it is important to be aware of the long-term management of COPD in making decisions regarding the acute management of an exacerbation of COPD. Many hospitals and community health units will have a COPD outreach programme which aims to manage patients with COPD in the community insofar as possible.

Clinical Features

Typical symptoms of COPD include dyspnoea, cough & sputum production. In an acute exacerbation, these symptoms are likely to worsen or change in nature, e.g. increased sputum production with a change in colour. Infectious exacerbations may also present with fever, rigors or malaise.

Patients may require supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturations or for patients on LTOT, they may have an increased oxygen requirement.

Differential Diagnosis

Respiratory

Asthma Exacerbation (if past medical history unclear)

Pulmonary Embolism

Pneumothorax

Other

Anaphylaxis

Cardiovascular

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Acute Pulmonary Oedema

Clinical Investigations

Bedside

ABG

May show type 2 respiratory failure

Acidosis

Hypercapnia

Hypoxia

ECG

Often tachycardic

Help rule out other pathology

Laboratory

FBC, U&E, CRP

Raised WCC suggestive of infection but may be raised in context of steroid use also

Raised CRP may also be suggestive of an infectious process

Blood Cultures

If patient is pyrexic at presentation, blood cultures can help direct targeted antimicrobial treatment in the coming days

Radiology

Chest x-ray

Order a portable x-ray for patients with a markedly increased work of breathing who need management in Resus

Findings for COPD are non-specific but may include flattened hemidiaphragms due to hyperinflation and increased bronchovascular markings

Acutely, a chest x-ray is useful for ruling in consolidation suggesting an infectious exacerbation and for ruling out pneumothorax, pulmonary oedema or other causes of shortness of breath.

Management & Disposition

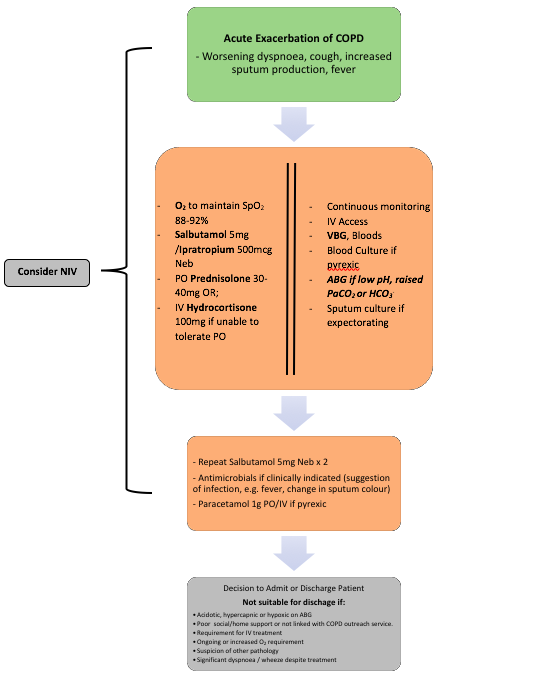

All patients presenting with a markedly increased work of breathing or hypoxia should be managed in resus. Give supplemental O2 to target an SpO2 88-92%. Avoid over-oxygenation as it is thought to depress the respiratory drive in patients with COPD.

Continuous cardiac and SpO2monitoring should be in place and IV access secured. It is useful to draw a venous blood gas when IV access is obtained to assess the pH and PaCO2 initially as these differ very little from an arterial sample.

If the patient has a markedly increased work of breathing, is acidotic (pH <7.35) or hypercapnic (PaCO2 >6.0kPa) on VBG, an ABG should be obtained.

Give nebulised bronchodilators, corticosteroids (PO or IV if unable to take PO), antibiotics if indicated and anitpyretics if the patient is febrile.

Non-invasive Ventilation (NIV)

Non-invasive ventilation is commonly used in severe exacerbations of COPD, particularly where the patient is acidotic and in type 2 respiratory failure (↓PaO2, ↑PaCO2+) as per the ABG.

Providing positive pressure ventilation offloads the effort of breathing from the patient and allows oxygenation in a tiring patient. It is a useful adjunct in the treatment of exacerbations of COPD however there are important considerations prior to initiation.

Typically, patients with an exacerbation of COPD will be commenced on Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP).

Indications for NIV

Acute exacerbation of COPD with acidosis & hypercapnia, with or without hypoxia

On maximal medical therapy

Senior review prior to initiation

Contraindications to NIV

Cardiac/Respiratory Arrest

Facial/airway burns or airway obstruction

Pneumothorax

Risk of vomiting or aspiration

Relative contraindications / cautions with NIV

Reduced GCS/confusion

Excessive secretions

Hypotension

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2020 Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GOLD-2020-POCKET-GUIDE-ver1.0_FINAL-WMV.pdf

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – Radiopaedia Reference Article https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-1?lang=us

Osadnik C et al. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017

This blog was written by Dr. James Condren and was last updated in October 2020